The first time I saw "Mandingo" a weird thing happened. I couldn't shake the discomforting feeling that accompanied it. I'd tracked down dozens of hard to find cult movies like "Beyond the Valley of the Dolls", "Emmanuelle in America" and "The Devils" that pushed the limits of shock value and taste, but this picture stuck with me. And not in a good way --

Growing up in Tennessee I saw a romanticized version of the old south - golden plantations filled with love and grace - "Gone with the Wind" was my barometer more or less. When I took a southern lit class at university I began to realize how many aspects in the slave culture of the old south had been glossed over. The course gave me a dry, logical examination of the passive racism inherent in a lot of the great writers of the region. I resisted at first due to pride, but I eventually came around to my prof's way of thinking.

Believe me, there's nothing dry or logical about Kyle Onstott's novel or Richard Fleischer's screen adaptation of "Mandingo". While the novel is overlong and moves at a leisurely pace, the film is like a bullet train - packing every brutal truth about human bondage and commerce into two hours of unrelenting suffering. Both the white and black characters are doomed to horrific fates, trapped within a system that dehumanizes them to the point of blind adherence to the very thing that enslaves their minds and bodies.

As hard to watch as it was, I couldn't deny its repellent power. After looking into the history of the film (it was practically buried by the studio, having only one VHS release at the beginning of the VCR explosion in the early eighties) I realized it was one of the most critically reviled motion pictures of its era. I was surprised - yes, it was unflinching and disturbing - but I felt its profound effect on my psyche proved its inherent value. If its 1975 box office take was any indication, audiences around the world felt the same way.

It finally got a small release on DVD last year so now you can decide for yourself.

Just so you don't think I'm some kind of sadist, I've included a fine critical re-evaluation by film journalist Robert Keser --

from Michael Weldon's Psychotronic Film Guide

the controversial poster art

The Eye We Cannot Shut: Richard Fleischer's Mandingo

by Robert Keser

Robert Keser teaches film at National-Louis University in Chicago and is associate editor of Bright Lights Film Journal.

“The whole slave story has been lied about, covered up and romanticised so much that I thought it really had to stop. The only way to stop was to be as brutal as I could possibly be, to show how these people suffered. I’m not going to show you them suffering backstage—I want you to look at them”. – Richard Fleischer interview (1)

“In a rigidly hierarchical society, sex – which respects no barriers and obeys no laws—can at any moment become an agent of chaos”. – Luis Bunuel in My Last Sigh

It is three decades since Mandingo burst onto the world’s screens in 1975, a time before microchips and multiplexes, and the very year that introduced Betamax video, yet the film’s uncompromising depiction of the moral wreckage caused by the slavery system remains undiminished. Directing his 38th feature, and arguably his finest, Richard Fleischer achieved an ideal balance between the personal and the historical, the individual and the collective, the emotional and the economic. Unafraid to offend with its depiction of casually virulent racism, the film has basically remained unseen since its first run, apart from an early VHS release. For a Fleischer retrospective in 1999, the American Cinematheque in Los Angeles had to send to England for the only surviving 35mm print of this now quintessential 1970s film. Produced when major Hollywood studios were willing to risk funding projects of uncommon honesty and historical awareness, Mandingo reflects its exact historical moment just as it unflinchingly confronts all three hot wires of American history—race, class and gender— to dramatize a squalid chapter of capitalism without restraints.

Nor has time blunted the critical edge of this remarkable and deeply political film, long championed by Robin Wood as “the greatest film about race ever made in Hollywood” (2). Without sentimentality or official pieties, Fleischer uses an unbridled and passionate melodrama to lay bare how slavery, the economic enterprise that turns humans into commodities, could not but distort the entire web of human relationships enabling it. To appropriate a phrase by John Berger from another context, Mandingo uniquely serves as “the eye we cannot shut”, the persistent vision of competing powers – the slave’s physical strength (and by extension sexual potency) against the master’s sovereign power to define reality and decide life or death. Widespread audience acceptance at the box office surprised even its makers (the director himself said that “I was really not prepared for the great success of the film”). (3) Contrary to popular formulas in Hollywood, Mandingo provided no conventional heroics or even moral growth and made no attempt to manage audience reactions with distancing irony or historical panaceas.

Perry King and Susan George

It also remains an unashamedly secular vision through the lens of 1975, joining such key films of that year as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Barry Lyndon and Dog Day Afternoon, and social critiques from the year before like Chinatown and The Conversation. The fall of Saigon, the outbreak of the Lebanese civil war, and the Khmer Rouge seizure of a U.S. ship, made a heady political backdrop, as did the (still unsolved) murder of Pier Paolo Pasolini and the Manson family’s attempts to assassinate the U.S. president. At that year’s Oscar ceremonies, Bert Schneider, producer of Peter Davis’s Vietnam critique Hearts and Minds which won for Best Documentary, took the opportunity to read a telegram from the Viet Cong (the contemporary equivalent of congratulations from Osama bin Laden). Clearly, movies were offering no easy escape hatches, and Mandingo firmly refuses any reassurances that the system works. If the film points toward liberation, it is simply by exposing the social mechanisms that supported racial and patriarchal domination.

While providing a baroque historical cap to end the then flourishing blaxploitation genre, Mandingo also undermines Hollywood’s fraudulent plantation romances that date back to silent cinema, notably Birth of a Nation (1915) and successive versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. During the Production Code’s heyday, corseted depictions of Southern honor and chivalry among the juleps and magnolia blossoms became especially popular with films like So Red the Rose (1935), Jezebel (1937) and Gone with the Wind (1939). Their black characters—grotesquely subservient major domos, protective mammies, and cheerfully ignorant housemaids—pale next to Mandingo’s victims, driven to tragedy by the racist and sexist humiliations of the slave system. (4)

Mandingo’s stage is Louisiana in 1840 (the year of the Cinque mutiny trials dramatized in Spielberg’s inflated Amistad, 1997), a time and place where race was destiny for blacks. A slavebreeding plantation is run by old Maxwell and young Hammond, the father crippled from rheumatism and the son lame from a leg injury.These are no morally anguished slaveowners, like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, but pragmatic businessmen plying their enterprise with the unshakable entitlement of Wall Street brokers today. Their prize acquisition is Mede, a “Mandingo” (the name is possibly a corruption of the “Mandinka” people of West Africa), a “brand” of slave coveted for his strength and potency. After Hammond weds a white woman (Blanche), he prefers to bed a slave (Ellen), setting in motion a drama that builds with intensity from hot confrontations and whippings to lynchings, infanticide, poisoning and pitchforking: enough murderous resolutions to fuel a grand opera.

With bath scenes and full frontal bedroom encounters, both female and male, this already incendiary project broke additional taboos by presenting two incestuous couples – a white brother and sister, mirrored by a black brother and sister. These are intercrossed with two couples engaged in miscegenation – one white male/black female couple, paralleled by one black male/white female. National film reviewers took this subject matter as reason enough to administer an official flogging, denouncing the film as one step above porn, a kind of hoopskirt Caligula blamed on producer Dino De Laurentiis. (5)

Perry King and Brenda Sykes

Thus, Variety dubbed it “embarrassing and crude…cardboard tragedy” but mistakenly forecast business would be “doubtful even in lesser exploitation markets” (6), while Vincent Canby deemed it “steamily melodramatic nonsense”. (7) Ten days later, the New York Times critic returned to Mandingo in a special feature called “What Makes a Movie Immoral”, arguing that “[b]ad films—films I don’t like—are immoral”:

[W]hat the camera sees is enough to make you long for the most high-handed, narrow-minded film censorship. “Mandingo” has less interest in slavery than ‘Deep Throat’ has in sexual therapy. It is as silly as ‘The Little Colonel’ but much more vicious. While the poor darkies are singing on the soundtrack, they are being beaten, humiliated, denied, raped and murdered onscreen, with the kind of fond attention to specific details one more often finds in the close-ups employed in pornographic films. This one is strictly for bondage enthusiasts. (8)

Not driven by literary respectability, Mandingo confounded critics who could not accept a serious statement about the socio-economic order in the form of a melodrama sans big speeches or messages embedded in dialogue. What’s more, the dramatic extremes of the plot, above all its heightened depiction of Blanche’s sexual frustration, continually risk making the film look ridiculous, no less than the use of archaic vernacular—such as “wenches” (black women used as bed partners) and “suckers” (their offspring).

In his capacity as both director and co-scenarist, Richard Fleischer reacted with passion, defending his artistry against reviewers who were unable to address racist subject matter that felt too raw (and may still be so):

The thing that is infuriating to me is that the critics become blinded by their own dislike of the subject. They may loathe the story, but then they say that the photography was bad, the sets were lousy, the costumes stank and that the writing was rotten. I can defend all of that. I can defend the direction, and everybody said the direction was terrible, inept. I really don’t think you can criticise a lot of things in the film as being badly done. You may hate what it is or what it says, but you can’t say it’s all rotten. It’s just not true. (9)

Indeed, this negative critical reception has shut Mandingo out of the national conversation about race, yet its indictment of top dog morality seems more relevant than ever. With no villainous power-hungry individual as a repository of the plot’s evils and no true hero with a tragic flaw, the system itself is the flaw that entraps and destroys its participants. Mandingo bears poignant witness to how this impersonal and unforgiving economic apparatus closes its jaws on each player and then bites down. The script’s genius—not too strong a word—is to fuse melodrama into social critique, creating a hybrid where sexual relationships are poetic correlatives to economic ones, acredible match as procreation formed the basis of the business. Mandingo is two entities at once: the economics contains the melodrama, while the potboiler is the repository of all the sexual conflicts and betrayals that reveal how the lucrative enterprise worked on a human level. As such, its pulp proves more useful than all the allegory and postmodern finger wagging of Lars Von Trier's Manderlay.

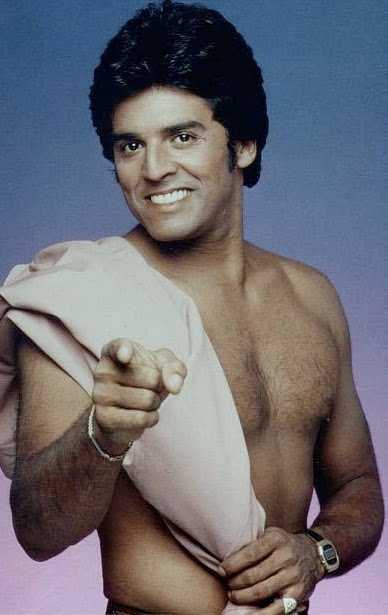

professional boxer turned actor Ken Norton and Susan George

At the very opening, the film literally gets down to business in a marketplace for slaves and mules, where buyers act out the insult of commodifying humans by examining the mouths of the topless men and women, forcing one male to bend over and pull down his pants, another to enact tricks like a dog. Men operate the slavebreeding farms, though the marketplace scene shows a middle-aged German woman, ostensibly a model of respectability, slipping her hand into the loincloth of a “black buck” for sale, evaluating the goods as a housewife might squeeze a tomato at the supermarket. In Mandingo’s complicit world, no one is an onlooker, so there’s no way out short of total revolution (Yankee abolitionists are shadowy troublemakers here and the Nat Turner rebellion a decade in the past).

In Wood’s words, “The entrapment is all pervasive: no leading character acts freely, none can break out of the ideological system the film defines”. (10) Just as the sun shines with equal brightness on slave and owner alike, all are equal victims of power. The owners try to wring out profit by regulating and rationalizing the “chaos” of sex even while they are themselves sexually enmeshed with their “property”, and only the slaves test the bonds of power. No one else questions it, anymore than people today question the economic order that renders them helpless in the face of privatizing, downsizing, outsourcing and conscription. Few living under naked injustice realize that life could be materially different, but wait for history to turn to the propitious moment for change.

Transmuting pulp to tragedy, Fleischer and scenarist Norman Wexler outshine their source, the independently published 1957 bestseller (5 million copies sold) by dog breeder Kyle Onstott. Mandingo was the fist in a series of slavebreeding novels (continued by other writers) called the Falconhurst trilogy. Also utilizing a stage adaptation by Jack Kirkland, Fleischer says, “I locked myself up with Norman Wexler for two weeks at the Plaza Hotel, and we wrote a complete new script” (11)

The Harvard-educated Wexler—author of such significant cultural provocations as Joe (1970), Serpico (1973), and Saturday Night Fever (1977)—counts as a key figure in the decade’s films, and had already been arrested in 1972 when the FBI learned that he was planning to assassinate President Nixon. Along with incidental changes to the book (altering the ending and excising characters, such as a masochistic boy slave who begs Hammond to beat him) and additions (the honeymoon in New Orleans, the public fight scenes at the brothel), Wexler crucially introduced the growing consciousness of rebellion among the slaves. No halos hover over these believably realistic blacks of their time and circumstances, never portrayed as martyrs but people enduring what they must to stay alive in the grip of economic terrorism. Wexler would continue this narrative by scripting Steve Carver’s Drum (1976), the now almost vanished follow-up to Mandingo, wherein castration and homosexual panic ignite an outright rebellion.

James Mason and Susan George

The more sympathetic Hammond (softened from the book’s depiction) is the human face of the system but also embodies its contradictions. In the golden-haired softness of actor Perry King, he is tender with black women, defending them even as he uses them. He commits to his mistress (“No one, black or white, [is] gonna take your place”) in a kind of surreptitious wedding vow. Furthermore, he compassionately refuses to allow the breaking of family ties among the slaves, argues against the employment of incest, and stands ready to sacrifice profit to stop a brutal beating of Mede. Yet he remains willing to punish a slave caught learning to read (in the book, the whipping resulted from stealing whiskey). Basically, father and son represent the fundamental American opposition of conservative vs. liberal, both serving the same power structure and both rejecting any challenge to it.

When his machismo is challenged by the two equal losers from his standpoint—

the white woman and the black man—the crisis peels away Hammond’s velvet glove, revealing his essence as he reverts to violence, precipitating the final wave of tragedy. Casting aside his slave mistress Ellen, he cruelly ruptures their relationship by enforcing his racial privilege: “Don’t think because you get in my bed you’re anything but a nigger”, acting to preserve his birthright. Mede voices the disillusion outright: “I thought you were better than a white man. But you is just white”. A benign despot with an attractive smile and surface compassion is a despot nonetheless.

Sex drives this plot forward, and miscegenation colors the movie (the word itself has fallen out of date, but the taboos are deeply rooted; the first film ever shown in the White House, The Birth of a Nation, pivoted on the imminent rape of a white woman by a black man and the ensuing revenge). Desire respects no socio-cultural controls, so when sex crosses hierarchical boundaries, the system cannot maintain its logic and physical pleasure becomes the seed within that will kill it. As the family business requires an heir to perpetuate its control, Hammond is expected to procreate as much as any slave. In the event, two babies result from mixed parentage, and both are destroyed by whites.

Mede (Ken Norton) at the slave market

A slave to the gender role assigned to her by hypocritical male values, Blanche represents innocence betrayed and distorted, unable to defend herself because the truth about her loss of virginity would reveal her brother’s abuse. Fleischer’s editing associates her with brothel prostitutes, including one blonde who strongly resembles Blanche: when she propositions Hammond, she has no more success than his wife does. Never whitewashing her racist core, Fleischer contrasts Blanche’s delicate porcelain beauty with her tough-minded struggle to survive, her cultivated manners against her selfish drunken rants. Isolated in her bedroom, the only space she effectively controls, and spurned by her husband, she rages with operatic fury, cursing and lashing Ellen down the stairs (“I’m gonna whip that sucker out of you”) until she finally orders Mede into her featherbed from a combination of physical longing and pathetic emotional hurt.

Mede becomes the conduit and crossroads for all the protagonists’ aspirations. To Maxwell, he is the prized “Mandingo” possession, while to Hammond, Mede is the master’s personal pugilist (boxing, a traditional survival route for black men, resembles prostitution as a selling of the body, as two big fights take place at Madame Caroline’s New Orleans brothel). To Blanche, Mede is the master’s phallic surrogate, as Shimizu suggests.(13) To the runaway slave Cicero, Mede must evolve to consciousness of the interracial exploitation (“How you’all feel laying here chained while white men walk about, do his pleasure with a black girl?”) and then fight back. Since individual revolt inevitably leads to failure, Cicero ends up lynched, but his final words still challenge Mede to rebel: “Leastwise I won’t die like you gonna die, like a slave”. (He models insurrection with his final words to the whites: “After you hang me, kiss my ass”).

Challenged by his fellows (“When ya gonna learn the color of your skin?”), Mede is unable to analyze his options clearly, and in that sense Ken Norton’s amateurishly guarded performance is effective (Fleischer protects him by reducing his dialogue to a minimum). Yet, in Robin Wood’s words Mandingo’s blacks “are never depicted as stupid or unaware; if they are ‘helpless’, it is purely because of social circumstance”. (14) Fleischer carefully stages preludes among the slaves, showing their preparation before whites enter the scene, as when a mother bathes her daughter while advising how to deport herself at her deflowering by the young master. Even in a disturbing scene where Blanche’s brother whips his slave girl sexual partner, the director unfailingly foregrounds the girl’s feelings (the camera shows us the shock and pain on her face).

Towering over his peers by dint of sheer productivity and longevity, he has been a survivor in a Darwinian competition that too often devoured its talent. With no great love stories (even Girl on the Red Velvet Swing concerns obsession more than passion), Fleischer’s world produces few heroes, and none without flaws. His films carry a melancholy aura as they face the violence of life directly, whether an axe lopping off Tony Curtis’s hand in The Viking or George C. Scott turning his revolver on himself in The New Centurions. In Mandingo, the hothouse intensity and nightmarish depiction of slavery conjures the mundane horror so strikingly conveyed in The Boston Strangler and 10 Rillington Place.

Motifs of eyes and looking recur in Fleischer’s work, back to The Narrow Margin, where cops and criminals are constantly looking, down the corridor or out the train window, viewing action reflected on an adjacent surface or watching a car speeding on a parallel road. Eyesight is lost for Anthony Quinn in Barabbas and Mia Farrow in See No Evil, while Kirk Douglas loses an eye to a hawk’s claw in The Vikings, with an explicit indication that he has been blinded for his vanity. In Mandingo, Maxwell suggests that the slave Mem be blinded for the crime of learning to read, though Hammond averts his eyes from the eventual whipping.

Fleischer celebrates the power of looking in Mandingo’s tender bedroom scene, a beautifully edited micro-drama of unmet eyeline matches, scissoring between Hammond insisting that Ellen meet his gaze (“You’re looking away from me. I can’t see you. Put your eyes on me”) and the woman resisting, until she finally joins his eye as he physically pulls her into his frame in a two-shot. Andrew Britton calls this “surely one of the most beautiful and moving love scenes in the cinema—moving in the complexity, depth and honesty of its emotion, superbly realised by Fleischer and his actors.” (15)

The director’s early work in newsreels and gag-compilations from silent comedies depended on intensive editing, and his mastery of staging action for the editor’s accommodation shows in the brilliantly shot no-holds-barred combat between Mede and the slave Topaz at Madame Caroline’s brothel (Mede must battle for his master just as the slaves in Barabbas had to fight each other in the gladiatorial circus at the behest of the emperor). Framed by close crowds, the men fight, scratch and gouge furiously to the finish (recalling the lightning cutting of the stateroom struggle in The Narrow Margin), until Mede bites through his opponent’s jugular (another step in his growing consciousness as he concludes that “nothin’s worth all this fightin’ and killin’”. Rather than evoking the claustrophobia of these people unconsciously sealed in a social order with no escape, Fleischer depicts wide open spaces evenly illuminated, an existential hell with no way out for them (where can they run?). For the same reason, the film spends little time detailing the accoutrements of coercion—the clamps, clasps, leg irons—opting for the much subtler point that rebels are kept in line by the sheer pervasiveness of the system. Fleischer told his lighting cameraman that the image we should keep in mind was a beautiful wedding cake that’s filled with maggots, so that when you’re a distance away from it, it’s very beautiful and romantic, but when you get up close, it’s horrible. . .(16)

Cicero's (Ji-Tu Cumbuka) brutal death

Outside, clouds hang low with humidity over the earthy brown landscapes hung with silvery green moss. This is a lateral world of low buildings, where life was lived close to the ground, and no higher than a second story. But what one remembers are the dark spaces that house the tragedy, the nearly empty interiors of the Maxwell mansion, with no pictures on the walls (only mirrors) in the stylized underdecoration favored by production designer Boris Leven (Shanghai Gesture, Giant, West Side Story, and New York, New York). With its half-empty rooms in darkness, and wide-angle distances between the players, the mansion seems like a visual correlative to their human estrangement in the moral shadows.(17)

With his cinematographer Richard Kline (in their fifth and final collaboration), Fleischer goes to pains to compose shots that join indoors and outdoors: even the slave cabins are roughly built so that light bleeds through the cracks between the planks, denying any meaningful privacy. It’s no better in the mansion, where not much that transpires behind closed doors remains secret in a houseful of attentive servants whose continued welfare depends on the moods and disposition of the masters.

Narrative is a stream in Richard Fleischer’s films, his players even literally riding the bloodstream as in Fantastic Voyage. Whether constructed with hefty flashbacks (which take up half of Between Heaven and Hell, for example) or proceeding straightforwardly as in Mandingo, many of his films create a perceptual continuum that flows in long takes and restlessly traveling camera shots. The director said that

I wanted the camera movement to be very elaborate. The camera is very restless and the outcome is the kind of languid feeling of the South. There’s no motivation for the camera moving but it’s creeping all the time, even in close shots. (18) If a single sequence could hold the key to his style, the gathering of slaves for the march to market shows Fleischer working at the highest level of fluid staging and dynamic camera deployment, blocked and synchronized with such sophistication as to look effortless and unobtrusive. There are a hundred ways to stage such a scene, but what Fleischer chooses is one unbroken tracking shot, almost two minutes in length, that moves laterally, then down and then up, finally pulling backwards and ascending high. Maxwell walks from a slave cabin, oblivious to the tearful goodbyes of slave families that will be separated, then Hammond enters from the background as the camera keeps gliding along the lines of family members weeping at the scenes of parting, pausing only slightly to observe emotional moments, micro-dramas of anguished farewell that recall the emotional weight of John Ford’s images of departing militia and soldiers in Drums Along the Mohawk (1939) and Rio Grande (1950). For the first time, Hammond asserts his authority over Maxwell by allowing a mother to rejoin her baby, and then reassures Ellen (I'm not going to sell you. I crave you to come with me.") As he mounts the carriage, the camera doubles back its route, rising when he stands up in the wagon.

Immediately following a closeup of a despairing mother falling in the dirt as she runs after the wagon, a second complex tracking shot begins from the mansion’s second story veranda, the camera turning jittery as it pans to Blanche’s face watching Ellen ride behind Hammond. Having just wept with shame at Hammond giving his slave mistress the earrings that match Blanche’s necklace, this becomes the last straw that provokes her to adultery and drives the plantation into moral chaos. Blanche can be read as a sister to Pearl Chavez in Duel in the Sun (1947), “a feminist claiming the right to lust, just like a man, a revolutionary underclass trembling on the edge of an anti-American crusade, if only she’d read Marx” (19)

To score this turning point, Maurice Jarre crafts a blues sung by Muddy Waters, but elsewhere his wind-up music box waltzes (trademarked in David Lean’s Doctor Zhivago, 1965) now sound quite dated, though drums beating alongside the snapping rhythms of African thumb instruments are more effective.

To understand how Hollywood films changed between the 50s and the 70s, one need only compare Mandingo with Fleischer’s still compelling Between Heaven and Hell from 1956, two films that mirror one another in social milieu and long-take stylistics yet come to totally opposite conclusions. At the center of both sits a silver-spoon plantation prince, Robert Wagner in the earlier story, treating his sharecroppers like a slaveowner (“They have to be kept in their place”). The plot sends him to war in their company to teach this spoiled and insensitive exploiter to value his employees, thus ensuring a happy ending (“Croppers will be better off after the war,” he vows. “Mine will, that’s for sure. I used to be rough on my croppers. Didn’t know any better”).

Almost twenty years later, his counterpart In Mandingo starts out as a kind of compassionate conservative, but physical and economic forces compel Hammond to revert to type and destroy his “property”. Equally in contrast, the wife in Between Heaven and Hell has a minor role but exerts a sensitizing influence, while Mandingo’s Blanche precipitates unstoppable destruction. Arguably the difference between a routine studio-driven assignment at Fox and a personal commission that Fleischer accepted, the 1956 film accepts that sharecropping works, but the slave system is inherently evil according to 1975’s view, not a time with patience for traditional excuses.

The slavery theme recurs in Fleischer’s output, with The Vikings anticipating Mandingo by following a white man and his African companion who are escaped slaves (while a blonde princess is esteemed and protected for her virginity), as well as Barabbas, telling a slave’s story from the public market through a Dantean stint in hard labor. A few years later, Fleischer himself would endure sunstroke to dramatize the modern slave trade in Ashanti, but losing focus in the process.

Producer Ralph Serpe, Laura Misch, and Richard Fleischer on the set

James Mason, Fleischer’s darkly charismatic Captain Nemo in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), was well into his character actor phase in Mandingo. Though top-billed, Mason plays a peripheral character, a crafty old flesh-peddling capitalist who is perfectly willing, for the sake of profit, to ignore the genealogy tables and order an incestuous coupling. Here forsaking his sonorous voice and oblique delivery for a jambalaya accent, Mason makes this role a neat counterpoint to his isolationist in Robert Rossen’s underrated Island in the Sun (1957), the aristocrat tormented to discover his own black blood.

As a director of performances, often rendered with great delicacy, Fleischer never sells his actors short, drawing good work even from undistinguished actors, like Terry Moore in Between Heaven and Hell. Entrusted with ensembles like Neil Diamond, Laurence Olivier and Lucie Arnaz in the hoary melodrama The Jazz Singer, or Arnold Schwarzenegger, Grace Jones, and Wilt Chamberlain in the medieval adventure Conan the Destroyer, Fleischer unites these disparate talents into some presentable coherence by sheer force of professionalism.

Surprisingly, none of the principal actors flourished in film after Mandingo. Perry King (grandson of Maxwell Perkins, distinguished editor of Hemingway, Fitzgerald and Thomas Wolfe) moved into TV movies and mini-series. Susan George, best remembered as the double-raped wife in Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971), soon retired to England to raise horses on her Arabian stud farm, with no apparent irony, while Ken Norton did not turn his 1973 boxing defeat of Muhammed Ali into an acting career, starring only once more in Drum, sequel to Mandingo.

Yet King and George give exemplary performances in Mandingo. When Hammond sees his wife’s black baby in the crib, Fleischer registers the man’s profound anger in medium close-ups as Perry King’s body stiffens with mounting intensity, then without a single word of dialogue, the camera moves to Blanche as Susan George tightens and recoils as she apprehends what will happen. In a powerfully hushed death scene, and with unexpected tenderness, he feeds her poisoned wine, as she touchingly surrenders to her fate with a last embrace.

This winds the springs tight for the memorably harrowing finale as the camera races alongside the avenging Hammond in a sweeping tracking shot that crackles with machismo betrayed and property rights threatened. Nothing can stop the tragedy: this is the brutal reality of how the system works, enacted before our eyes.

In today’s climate that glorifies accumulation of private wealth, no matter the cost to others, Mandingo would be unlikely to win funding, certainly not in the mass market, which requires the triumph of the oppressed. How many Hollywood productions mine the tension between human rights and the profit motive?

"Lone Wolf McQuade" director Steve Carver's lackluster sequel

For all its provocations, Mandingo paved the road only for TV’s sincere but sanitized Roots in 1978, the epic mini-series important as an acknowledgment of black history and as a shared cultural experience, seen and discussed throughout the country. What has been lost since 1975 is the ability to consider a structural analysis of society rather than individual arias of victimization. What remains is the stubborn adherence of white privilege, still flying its Confederate flag while cast-iron pickaninnies stand guard at the suburban driveway, so we cannot shut out Mandingo’s fundamental truth that racial tensions were only slowed by the Emancipation Proclamation, not erased (dramatized with less strain than Paul Haggis’s Crash)

From feudal serfs to outright chattels to harried sweatshop workers in maquiladoras around the globe, history bears witness that slavery is no temporary derangement of human nature but rather a function of the species’ will to power. The present ban on owning human property represents a fragilely maintained hiatus of only a century and a half. Mandingo value increases insofar as it makes the audience question the morality of every system and remain alert to the displays of breathtaking venality that constitute today’s social coercion (see films like Lilya4Ever and Darwin’s Nightmare). It requires no great leap to link plantation injustices to the drowned corpses mired in the sodden ruins of present-day Louisiana, a reality we cannot refute, an eye we cannot shut. Mandingo’s world, both 1840 and 1975, is past but its moral darkness now seems full of unfinished business for our own time.

Notes

(1) Interview by Ian Cameron and Douglas Pye, “Richard Fleischer on Mandingo” Movie 22, February 1976, p. 24

(2) Robin Wood, Sexual Politics and Narrative Film: Hollywood and Beyond, New York: Columbia University Press, 1998, p. 265

(3) Fleischer interview, p. 29

(4) Sad to say, Mandingo marked the screen’s discovery of the slavebreeding industry, though Anthony Adverse (36) gave glimpses of adventurers in human traffic, and Tay Garnett’s Slave Ship (37) mounted a still impressive sequence of white slavers forcing their African captives into chains for the horror-filled transatlantic crossing. Prior to Mandingo, only Herbert Biberman’s uneven (and almost unseen) Slaves (1969) had attempted a frank dramatization of the slave market industry. Since Mandingo, no other film has come close to its unsparing critique of slavery, not Haile Gerima’s folk-inflected Sankofa (1993), which evoked the lost African culture in the new world, nor Jonathan Demme’s boldly poetic Beloved (97) translating suffering into sensual imagery.

(5) Not infrequently tarred for his exploitation instincts, De Laurentiis absorbed much of the hostility against the film’s sensational aspects (but also deposited the profits). Critics conveniently overlooked that he had brought the world Fellini’s La Strada, Visconti’s Lo Straniero, Bergman’s The Serpent’s Egg, as well as such hard-hitting English-language productions as Lumet’s Serpico, Cronenberg’s The Dead Zone, Don Siegel’s The Shootist, Michael Mann’s Manhunter, and David Lynch’s Blue Velvet.

(6) Variety, 7 May 1975, p.48.

(7) Vincent Canby, New York Times, May 8, 1975, 48:1

(8) Vincent Canby, “What Makes a Movie Immoral”, New York Times, May 18, 1975, 11: 19

(9) Fleischer interview, “criticize”

(10) Robin Wood, p. 272

(11) Fleischer interview, p. 23

(12) Celine Parre ñas Shimizu, “Master-Slave Sex Acts: Mandingo and the Race/Sex Paradox”, Wide Angle, Vol. 21, no. 4 (October 1999), p. 50

(13) Shimizu, p. 46

(14) Robin Wood, p. 272

(15) Andrew Britton, “Mandingo”, Movie 22, February 1976, p. 11

(16) Fleischer interview, p. 26

(17) Andrew Britton traces American literary representations of “the appalling mansion” back to James Fenimore Cooper’s “The Pioneers” and especially Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” in “Mandingo”, Movie 22, February 1976, p. 3

(18) Fleischer interview, p. 29

(19) Raymond Durgnat and Scott Simmon, King Vidor, American, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988, p. 247.

Wonderful piece here. And I say this as a card-carrying member of the Society For The Rehabilitation of Mandingo's Critical Reputation. Great, informative writing.

ReplyDeleteI did my own piece on it awhile back:

http://scottisnotaprofessional.blogspot.com/2011/02/mandingo-1975.html