Cult Figures

By ARTHUR LUBOW

Published: August 15, 2004 - The New York Times

On Sept. 29, 1999, in the Wan Chai neighborhood of Hong Kong, a line of people, snaking from the street to a fourth-floor showroom, awaited admission to an exhibition of 99 customized action figures by a young designer named Michael Lau. In the combustible world of Hong Kong trends, this was something seriously new. Transforming hard-plastic, 12-inch action figures into pop-culture icons -- that was a familiar pastime for Hong Kong toy collectors. It had even become a little boring.

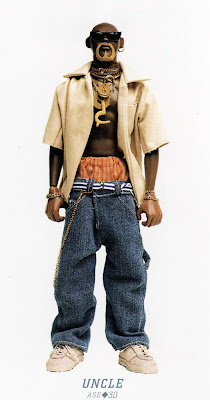

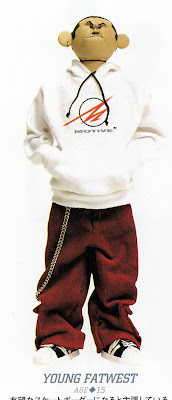

But Lau's grown-up toys were different. Using bodies he scavenged from dolls like G.I. Joe and molding original heads, hands and feet out of hard plastic, Lau had created skateboarders, surfers and snowboarders, decked out in baggy shorts, camouflage jackets, tentlike sweatshirts and of-the-moment sneakers, adorned with chains, earrings and tattoos, their hair in dreadlocks or pressed beneath bright-colored caps. ''Street culture and hip-hop culture and skateboard style were coming up,'' Lau explained when I met with him not long ago in Hong Kong. ''The culture included fashion, music, graffiti. It seemed really fresh. It is just like a uniform -- people in Hong Kong and Tokyo and Britain and the States all look the same.'' Sharply observed, exuberantly imaginative, Lau's collection of 99 ''Gardeners'' (named for comic-strip characters that he created the year before) looked just like the local hipsters who were looking at them, or the way those people wanted to look.

Lau's 99 Gardeners inspired other Hong Kong comic-book illustrators, graphic designers and ad-agency artists to start making their own figures. While a few Japanese cult boutiques had previously issued some limited-edition collectible toys, the Hong Kong designers engendered a craze. Over the next five years, riding on the wings of the Internet, such ''toys,'' as their enthusiasts call them, spread from Hong Kong, first to Japan and then to the West. Typically issued in limited editions of a few hundred, these toys are meant not for play but for display. They are valuable enough that many buyers leave a new purchase untouched in its box, hoping to preserve its resale value, which for a sought-after toy can quickly double or triple on eBay. Prominent toy artists in Japan, the United States and Britain, as well as those in Hong Kong, attract devoted fans -- typically, young men in their 20's and 30's who are ready to plunk down $100 or $200 for a toy, a small fraction of the original cost.

At one of the main outlets for these limited-edition figures, the two-year-old Kidrobot, which has stores in San Francisco and New York, toys often sell out in a few days -- or a few hours. Limited editions in different colors, typically in runs of 100 to 500 units, can be made for particular countries or specific stores. The perception of scarcity fuels the designer-toy market. Savvy toy retailers know how important it is to heighten that anxiety, but they turn the pressure tactic into a game. ''There was one toy that was available only if it was raining out,'' explains Paul Budnitz, Kidrobot's president. ''Another toy was available on Mondays only. It makes it really fun. I suppose it is good marketing for everyone. Everything here sells out.''

Youth-oriented fashion and entertainment companies like Nike, Sony and Levi's picked up on the fad, sponsoring exhibitions and licensing the artists' figures. The trendsetting Paris fashion-and-design store Colette has staged two exhibitions of designer toys, the most recent in June. Over the summer, Visionaire, a New York art-and-fashion publication, mounted a gallery show of designer toys; it will devote a characteristically lavish issue to the subject in November, with dolls customized by fashion designers, including Karl Lagerfeld, Marc Jacobs and Dolce & Gabbana.

Grown-up toys are making it big. But the positioning of a factory-made toy as a limited-edition art object is a particularly delicate maneuver. For artists designing toys, commercial success is a potentially fatal problem.

34-year-old with a ponytail and the wispy suggestion of a goatee, Michael Lau looks like an artist, and he seems to think of himself as one too. Lau is one of six children born to a chicken farmer in Hong Kong's New Territories; the family later moved to a public housing project in the capital. They couldn't afford store-bought toys. ''I sculptured Yoda out of cheap soap or made furniture out of newspaper,'' he recalled, as we sat and talked in his apartment overlooking a soccer field. (He spoke to me in Cantonese, and his girlfriend, Mickey Cheng, acted as a translator.) A talented draftsman, he found work after graduating from high school as a retoucher in an oil-painting factory, as a window-display designer for a department store and, finally, as a ''visualizer'' at an advertising agency -- the person who converts a concept into a sketch or a storyboard.

The visualizer he replaced at the Japanese-owned agency was named Eric So, who had also grown up poor in Hong Kong. So and Lau shared an enthusiasm for G.I. Joe dolls. Customizing toys was pure play, a way of expressing artistic talents that they were pursuing more ambitiously by painting in acrylics. In 1996, each exhibited at the Hong Kong Arts Center. The next year, Lau won a drawing prize in Hong Kong for the most promising artist. His career was going well, but he couldn't tell where it was going. ''I am looking at so many references,'' he said. ''It is hard to be the best in any area. It is difficult to find a point to break through.'' Unexpectedly, playing with toys would become his vocation.

Long a center for toy production, Hong Kong factories were, in the 1990's, succumbing to competition from cheaper labor on the Chinese mainland. As toy manufacture declined in Hong Kong, toy nostalgia flourished. At the high end of the market were Japanese airplane models, original ''Star Wars'' figures and first-generation G.I. Joes. All of these were vintage or antique toys, which, in the toy world, usually means an item that dates from the 70's. That decade, in Asia as in America, glows like a distant golden age for those who were children then, and the iconic figures date from the era's movies (Darth Vader), cartoons (Ultraman and Gundam) and cereal boxes (Cap'n Crunch, Franken Berry and Count Chocula).

All the prominent players in the Hong Kong designer-toy scene began as collectors of vintage children's toys, driven by a nostalgia for childhood and a delight in quirky design. One of the biggest collectors, Neco Lo Che Ying, staged a flea market in the summer of 1996 for fellow enthusiasts to trade and buy toys, and invited a few friends, including Lau and So, to exhibit their collections of vintage toys. Two years later, Mr. Lo -- as he is generally known, in deference to his pioneering role and relatively advanced age (44) -- gave Lau and So space to display their customized creations. By then, So was obsessively making Bruce Lee dolls, sculpturing the heads so that they better resembled his martial-arts hero and accumulating old magazine photographs to recreate Lee's authentic 1970's outfits. Lau was doing something more original. For a photograph that became an album cover for a local heavy-metal band, Anodize, he transformed five G.I. Joe dolls into cartoony renditions of the band's members.

More than his art shows, the album cover made Lau an insider's celebrity. In 1998, old friends from the ad agency where he'd worked invited him to contribute a comic strip to a trendy magazine, East Touch. Lau's strip depicted kids dripping with tattoos and attitude. He named them Gardeners. ''They are a group of people with their own culture, and they ignore other people and enjoy what they're doing,'' Lau offers by way of explanation.

That spring, he and Cheng used the prize he won for most promising artist: a trip to Paris. It was his first visit to Europe. In France for three weeks, he discovered with delighted astonishment a book about Jean-Marie Pigeon, who makes stylized sculptures of Tintin and other comic-book characters. ''Coming back to Hong Kong, I thought maybe it would be a good idea to try to turn the Gardeners into a 3-D format, the Tintin face on top of action figures,'' he says. He spent two months completing 10 figures for the convention, which Mr. Lo was now calling Toycon. He finished at the last minute and then collapsed with a high fever. It was worth it: the response was ecstatic. He was so pleased that, for his next art show, he decided to expand the Gardener population. ''It was supposed to be a painting show,'' he observes. ''I said it was 'mixed media.''' Because the year was 1999, he made 99 figures, which he worked on for nine months. The show not only made Lau's name; it also positioned toys at the center of Hong Kong street culture.

There was only one problem. None of the 99 unique 12-inch figures were for sale. Twelve-inch figures are made of hard ABS plastic, which is solidified in an expensive mold -- making them too expensive to custom-fabricate anything larger than heads, hands or feet. Another way to produce plastic toys is the rotocast vinyl method: vinyl plastic is injected into a cheaper mold and spun, producing a hollow object, which is then painted. Although rotovinyl toys can't exhibit the fine detail of ABS plastic, they are far cheaper and easier to produce. Because the mold is less expensive, designers can reconfigure the entire shape; they then have the advantage of not being constrained by the 12-inch anatomical form. Looking to transform the designer-toy movement into something commercially viable, Lau landed on vinyl.

Collectible vinyl toys were popularized in 1996 -- eons earlier, in this fast-moving universe -- by Bounty Hunter, a cult boutique based in Tokyo that combined the production of limited-edition urban clothing with a fetish for 70's pop music. That year the design gurus behind Bounty Hunter began selling limited numbers of vinyl toys that bore a discernible resemblance to such cultural landmarks as Franken Berry or a sailor on the Cap'n Crunch box. On the day of a toy's release, devotees would line up for blocks outside the store; the next day, in the resale market, the sold-out toys would be going for several times their original cost of $50. Still, that was in the street-culture hothouse of Japan, and these toys were a promotion for the coveted Bounty Hunter brand. Lau wondered anxiously if small vinyl versions of his 12-inch Gardeners -- standing on their own artistic merits -- could fetch 150 Hong Kong dollars (about $19 U.S.). ''He was so worried,'' recalls Wong Kim Fung, a manufacturer of high-end toys. ''I said: 'If you can't sell, bring it to me. We sell for $180.' Of course, all sold. Eventually on eBay they are raised to $1,000 [$128 U.S.].''

Taking advantage of their proximity to factories on the mainland, some Hong Kong collectors were already manufacturing 12-inch hard-plastic designer toys, and easily moved into vinyl toy production. Among the first were Wong Kim Fung, who is known as Kim, and Howard Chan. Both were toy retailers who, in early 1999, brought to market G.I. Joe figures that they had customized and accessorized into Hong Kong riot-squad policemen. The market responded favorably, rocket-powering the launch of their toy manufacturing companies: Kim's Three Zero and Chan's Hot Toys.

For a brief, brilliant moment, the future seemed unbounded. Starting in 2002, there were three Toycons a year, each lasting three days and playing to packed houses. The indefatigable Lau would introduce two vinyl toys on every day of each Toycon. It was a profitable business. Although Lau declines to comment on his income, the arithmetic is rudimentary. ''If he made 500 pieces for each style selling for 500 Hong Kong dollars apiece,'' -- about $64 -- ''he makes 250,000 Hong Kong dollars for each,'' estimates Raymond Choy, a toy manufacturer. In a sellout of all six at Toycon, he would take in 1.5 million Hong Kong dollars ($192,000 U.S.). For three annual Toycons, that adds up to almost $576,000 U.S. The cost of making a rotovinyl figure is a small fraction of the sales price, and Lau's Toycon figures were less than a small fraction of his total production. He was well on his way to millions.

In 2000 Lau signed a three-year contract with Sony to license his Gardener figures in Asia; and with Sony's help, he mounted a five-city exhibition of the Gardeners in Japan. Eric So was right behind him, turning his hand from customized action figures to vinyl toys that, notwithstanding their experimental flair (spindly arms and legs, unorthodox magnetic attachments) clearly owe a debt to Lau. These high-quality rotovinyl figures based on street-fashionable youth became known as urban vinyl. Soon it was as if every ad agency visualizer and comic-book illustrator in Hong Kong were designing toys -- all of them hoping to make it big.

The most successful Hong Kong toy designer after Lau and So is a three-man collaborative that calls itself Brothersfree. The Brothers zeroed in on uncharted territory -- Hong Kong working-class life. Their first customized action-figure in late 2000 was the team leader of a construction crew, a type they would see from the bus window as they went to their jobs at ad agencies or graphic design firms. The extraordinary detail in the Brothers' high-priced action figures (averaging about $200) sustains their popularity: a bank robber carries individually wrapped bundles of printed bills; a war correspondent totes a camera with interchangeable lenses. The Brothers' later vinyl toys, at a comparably high price, have sold less well. Customers perceive value in detail work more easily than they see it in creative design. They also know that action figures, with highly wrought accessories, are much harder for bootleggers in China to knock off.

As the field became crowded, with some 50 or 60 designers in Hong Kong alone, newcomers needed distinguishing styles or gimmicks. After designing some hip-hoppish figures that came too close to Lau for commercial comfort, Jason Siu began making dolls that resemble (and, in some cases, function as) stereo speakers. ''I want to make it my symbol -- speaker is Jason, Jason is speaker,'' he explains. ''I want my work to be famous and popular.'' Elphonso Lam, who in addition to his day job as a comics writer is the singer and lyricist for a Hong Kong punk band, has designed a vinyl toy of a chain-saw-wielding ghost and action figures of punk musicians. He is releasing his band's next album with a toy and a T-shirt.

Another toy designer, Colan Ho, says he hopes that his robot and spaceman figures will generate interest in the characters in his sci-fi graphic novels. Simon Wong, who has designed fashion collections for Esprit and CK jeanswear, is producing 12-inch figures that sport bead-laced string purses and leather-faced down coats. (Recently he obtained ''original 1970's polyester'' to line a denim outfit.) ''The goal is to attract fashion companies that would want to collaborate with me to do something -- a promotion item to put in the window or give away as premium gifts,'' he says. He says he dreams of eventually having his own fashion line. Meanwhile, pursuing a better-trod path to fortune, the brother-and-sister team of Wendy and Kevin Mak -- children of a manufacturer of plastic water guns -- have concluded that their toys, known as 2da6, are priced too aggressively. They produced their first toy, a teahouse waiter, in late 2001, as an adjunct to an online game. The game collapsed, but the toys persist, despite anemic sales. ''The cost of all these figures is too high,'' Wendy Mak says. ''Our future plan is to go for mass production, to Toys 'R' Us or Kmart.''

The mist of money has changed the atmosphere of the Hong Kong designer-toy scene. With eBay, price appreciation that in the traditional collectibles or art market takes years can occur overnight. ''In Hong Kong you have all these companies now that are mass-producing but trying to make it seem as if they're putting out limited-edition collectibles,'' says Jakuan, a New York toy designer and collector whose 360 Toy Group, a quiet storefront on the Lower East Side with a vibe very different from Kidrobot's, has been displaying designer toys since 1999. ''The market is saturated. You don't know what's good and what's not. That's what killed the comic-book market and the 'Star Wars' toys market. I think they're deceiving the customers. They're trying to market it as collectible, when it's really just a toy.''

Raymond Choy, 39, is typical of the new breed of Hong Kong designer-toy manufacturer. Like Kim and Chan, he began as a collector, with a special interest in the American toys based on the X-Men. But right from the start, what really drove Choy was the speculative frenzy. ''I am hooked on it, because a toy starts as $9 and then it is $100 U.S.,'' he says. ''It is like business. EBay also is turning into a very big support for the toy revolution. I see in the magazines how toys can be so much money in the secondary market.''

Unlike Kim and Chan, who aspire to fulfill a designer's vision, Choy searches out new artists who will be willing to collaborate on a profitable toy. Like other manufacturers, his company, Toy2R, makes use of technological advances that permit a factory to interrupt a run to change colors and create limited editions. For most of the Hong Kong artists, however, limiting the edition was a way to present the product as an art object and to maintain quality control. At Toy2R, a limited edition is merely a marketing ploy. There are so many different versions of Toy2R's Qees that the profusion becomes bewildering.

At the very moment the designer-toy trend is building strength in the West, it is already flagging in Hong Kong. ''I don't really buy toys anymore,'' says Takara Mak, who goes by TK and is the 25-year-old founder of two trendy Hong Kong magazines, Milk and Cream. ''I still spend time going on eBay, checking out what's going on, but I don't have the time or the force behind me to say I have to buy them every week. You used to see a photo and say, 'I have to get that tonight.' I don't feel that way anymore. I still like them, but there's too many of them.'' TK is reclining in his studio, which he calls Silly Thing -- a converted ground-floor warehouse that could double for the loft in the movie ''Big.'' It is decorated with customized skateboards and the cardboard stand-up figures that normally reside in cinema lobbies. A tall cabinet is filled with vintage ''Star Wars'' toys, and a flat-screen Fujitsu monitor lies beneath a glass-covered cutout in the polished plank floor.

Just two years before, at the height of the Hong Kong toy craze, TK inaugurated Playground, a 36-page toy-focused insert in the weekly Milk. ''It was the first time somebody did something on toys on that scale in a fashion magazine,'' he says proudly. Last December, he downgraded his coverage of toys. ''We thought with Playground, people twisted the idea we had in the first place,'' he explains. ''We don't want people to take toys in the wrong way. People buy to resell them. It's more like an investment than a thing you want to keep.'' Designer toys, which initially incarnated a youthful alternative culture, have been subsumed by the ruling, money-driven Hong Kong ethos. Still, Tomm Wong, the mastermind of Playground, resigned his position as editor in chief of Cream to start a new monthly devoted to toys. In homage to Lau, he plans to call it Garden. ''We want to build up a culture of how to play with toys, not how to buy and sell,'' Wong says bravely.

The highly motivated Lau continues to produce vinyl figures at a breakneck pace. He is working his way through a complete vinyl edition of the Gardeners (12 have been issued so far), as well as inventing another series of characters that he calls Crazy Children. Resourceful and ingenious, he has explored the potential of vinyl, innovating with rough surfaces that resemble wood or cardboard and creating a group with removable attire. He maintains that the word ''toy'' is misleading. ''We went to the Saatchi Gallery in London,'' he says. ''It's all toys, but in big size. If it's miniature, it's toy. If it's large, it's art.'' Who can argue? The stainless-steel bunny and the floral puppy of Jeff Koons, the anatomically perverse manikins of Jake and Dinos Chapman, the oversize child's firetruck and the naked family of Charles Ray, the whimsical clog-wearing dog of Yoshitomo Nara: aren't they just Brobdingnagian toys that have marched into art galleries and pasted labels on the wall?

Toys don't exhaust all of Lau's artistic powers. Over the summer, he designed the program for a local production of ''The Glass Menagerie,'' and he says he would like to do a theater piece of his own. ''I want to go back to painting, but Hong Kong is not the place for painting,'' he says. ''I want to do animation, but the cost is so high and you have to include too many people.'' This year, he inflicted a grievous body blow to the Hong Kong toy scene: he stopped appearing at Toycon. ''It is very boring,'' he says. ''I repeat it eight times already. I want to make a change.''

Lau now exhibits his work in his own gallery, located on the sixth floor of a commercial building in a popular shopping area that is worlds away from the crowded stores of the Mong Kok toy district. One afternoon in late June, there were six small toys on display, each on a plinth in its own vitrine. Nine toys from the series were being offered for sale, priced at a little more than $60 apiece. (Some other Lau works were also available.) Hip-hop music played softly. An attendant spoke on the telephone behind a counter. There was nobody else in the gallery. ''This is not the main market for the customer,'' says Chan of Hot Toys. ''He can just keep the old fans. You cannot get the new customer.''

Arthur Lubow is a contributing writer for the magazine. His most recent article was about the New York Philharmonic.

Correction: Aug. 29, 2004, Sunday

Because of an editing error, an article on Aug. 15 about designer toys from Hong Kong and elsewhere misstated the relationship between the cost of manufacturing them and their retail price, $100 or more. The cost of making them is a small fraction of the sales price.

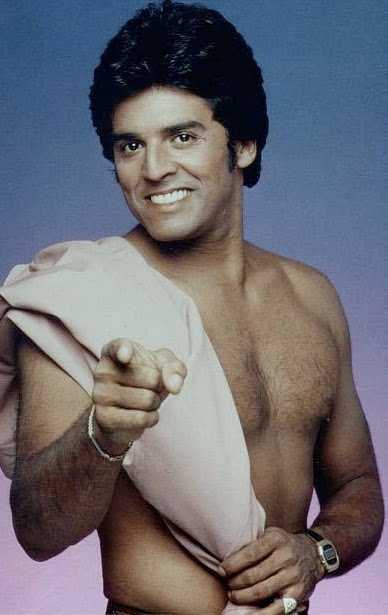

portrait of Michael Lau

No comments:

Post a Comment