SXSW: Mosh Pits on a Bridge at 3 a.m.

By MELENA RYZIK

Josh Haner/The New York Times

Thee Oh Sees perform on the Lamar Street pedestrian bridge.

AUSTIN, Tex. — “Should we just keep playing until the cops come?” John Dwyer, the floppy-haired frontman of Thee Oh Sees, said about halfway into the group’s set atop the Lamar Boulevard Pedestrian Bridge. It was after 3 a.m., and the crowd fist-pumped its assent, so Mr. Dwyer bent over his guitar, the lights of downtown flickering behind him, Lady Bird Lake below.

Thee Oh Sees, from San Francisco, have a long history but not much recognition outside the Bay Area (the group has changed its name several times). Mr. Dwyer, 35, is a veteran musician, having played with a half-dozen popular bands there, refining his sound with each one. Thee Oh Sees have the propulsion of punk and the whirl of psychedelia, and the foursome, occasionally joined on the bridge by a singer from another band, drew a few hundred people. A few hundred very enthusiastic people.

Though the group had done its professional best, lugging all of its equipment, down to the Oriental rug beneath the drum kit, to the center of the bridge and tried to supplement the streetlamps with some mobile lights, the vibe was far more chummy than polished. The group performed in a tight knot with the audience clustered inches around it. There was a mosh pit and even some crowd-surfing. At times the dancing was so hard the bridge shook.

At 3:45 a.m., Mr. Dwyer said goodnight, but the crowd chanted for more. “We don’t actually have any more songs, is the problem,” Mr. Dwyer said, before summoning up one more five-minute thrasher.

The shows on the bridge, an Austin tradition, have the feel of an underground, do-it-yourself endeavor, in the vein of punk houses and garage jams. But don’t be fooled: even these seemingly seat-of-the-pants happenings have a booker and sometimes a promoter (though they prefer to keep a low profile). In the past, word of a show was spread the old-fashioned way: via text message. Now, of course, it was Twittered. Earlier on Thursday night, whether the show was canceled or not – and who would be playing – was broadcast and debated online.

In the end the show went on, if not quite on schedule. It was Thee Oh Sees’ third show of the day. “We played one right before – we were late to come here,” Mr. Dwyer said, clearly spent after his sweaty, hourlong performance. The Bridge shows are an antidote to the many things that musicians gripe about during South by Southwest: the ultra-short sets, the crowds that are more interested in networking than listening, the focus on promotion. There are no corporate banners on the bridge (for now) and the shows can last as long as the musicians, or the authorities, want. But no money changes hands. “Hey, do you have any T-shirts for sale?” one newly minted fan asked Mr. Dwyer, who did not, and didn’t seem bothered by it either.

The police never showed during Thee Oh Sees’ show. Mr. Dwyer acted kind of chagrined. “I’m exhausted,” he said. “So I was kind of like, come on, cops. Take me to bed.”

All The Dread And Joy A Body Needs

Dec 8, 2009

Words by Sean Moeller

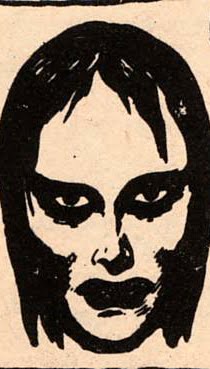

Illustration by Johnnie Cluney

Sound engineering by Shawn Biggs

Johnny Dwyer, the lead singer of the Bay Area psych/garage rock outfit Thee Oh Sees, has a naturally gifted voice for sputtering and spattering, reverb-clogged and fuzzed rock and roll music. It's so suited for the style, in fact, that we will from here on out, just refer to it as The Voice, with two instances of capitalization and insisting that it is a proper name. He has a sharp and high-pitched whine at times that just sounds like a young misfit trying to find his place in the world, thrashing around in its own skin and outsider world until something finally touches down.

It sounds as if its echoing back to us from the 1960s, out of those cheap microphones, the voice of a man whose time is spent slicking back his pompadour, who's into all of that British Invasion stuff, who's trolling around the Haight-Ashbury corridor looking for heroes, who's reading subversive novels by all of the brilliant, druggie fiction writers at the time and who's still been hanging out at the hamburger stands at night, prowling the loop for pretty girls to try and romance.

Thee Oh Sees are a band that incorporates all of the subtle references to rebellious, youthful rock and roll from generations back, boy-girl harmonies a la the Mamas and the Papas, as well as a knack for the ringing tunefulness of Buddy Holly - all of it touched with golden tones and then mussed up enough to not be too damned clear and straight-arrow. It's an angular and frazzled stab at meeting all of the different corners of early days rock and roll music - when it was called by adults and kids, sort of with a sneer and sort of with an undeniable pride, "rock 'n roll music" - together into some wildly uninhibited spin-out.

Dwyer inspires paranoia with his skuzzy vocals and at times makes you want to spit and others makes you want to grab a partner around the waist and just twirl around and around, in your socks, on a wooden dance floor. "Go Meet The Seed" is one of those dance on the wooden floor numbers and "Destroyed Fortress Reappears" is one of those spitting numbers that just makes you lower the tops of your eyelids and begin to get suspicious of everything, even that which you think you're familiar and friendly with. It doesn't really matter which mood Thee Oh Sees twist you into, as it all moves and it all gets the pores working overtime, soaking our clothing with dread and joy.

Album Artist: Q&A w/ Thee Oh Sees' Cover Man William Keihn

By Emily Rose Epstein, Tue., Mar. 9 2010 @ 7:30AM

To most San Franciscans, William Keihn is simply a comrade, sharing enthusiasm for the local music scene and a spot in the front row at shows. He sips thick ale, taps his foot, and applauds like the rest of us, smiling and occasionally singing along. But what most locals don't realize, much to Keihn's satisfaction, is that he is the man behind some of the most iconic local garage/psych album art of recent years.

Working with the likes of Thee Oh Sees on their albums Help and The Master's Bedroom Is Worth Spending The Night In, Keihn has crafted a style that is undeniably distinct. He has also cultivated an iconographic aesthetic rife with color and psychedelic chaos that exists as a product of the now, helping to give aesthetic structure to a current, vibrant underground culture in San Francisco.

All Shook Down chatted with Keihn in a Lower Height tavern about drugs as gateways to inspiration, album covers as myth makers, and the awesomeness of Cannibal Corpse's Back To Life.

At what age would you say you really came into a style that was your own?

When I was a little kid I drew a lot. I learned to make really appeasing art for adults. Then I went to middle school and didn't think I was any good. I was never the kid who was identified as the one who could draw. There only seemed to be room for the one guy who could draw the best Grateful Dead bear or draw a rad alien or something. I wasn't that dude, so I lacked the self-esteem necessary to project myself forward, but I kept drawing and drawing. I used to rip off Swamp Thing comics and just draw the entire comic series based on other comic books and things like that. Then in high school I started smoking a lot of weed and doing a lot of drugs and that kind of gave way to liberation for me to feel like I could be more expressive in my art. At that point I graduated school and moved away from my hometown and started making punk flyers for bands...Xerox art, in a really historically punk fashion.

When you began to collaborate with musicians and do more music-related art, did you go to the bands and musicians with ideas, or were people coming to you with ideas?

I would usually have a good idea of what I wanted to do and people took chances on me. I just always made myself available to do those things and a lot of people in bands don't have the time to consider all these different elements [besides] making music and performing.

Why does doing flyer and poster art appeal to you so much?

Part of what's appealing to me is that you can make them quickly, and they are easily accessible for someone to see, take, tear down, put on their wall, interact with in a tactile way, as opposed to a painting that you spend a lot of private time with. It's the quickest way to disseminate information. It's an equalizer because people who don't have printing presses can copy something and give it away. Some people say it devalues a single image, but it's either keep it singular, or share it with as many people as you can, and I like doing that.

People are probably most familiar with your album art for Thee Oh Sees. How did your relationship with them evolve?

I used to visit my friend in San Francisco when I was still living in Indiana and he lived with John [Dwyer] so I would stay at their house and he was really warm to me. We would have conversations about Providence, Rhode Island, because I always had a strong appreciation for Providence, due to the strong art presence there. We would talk about artists that we were mutually aware of are friends with. As a "thank you" for letting me stay at his house, I sent him some of my art through the mail and he connected with it instantly and wanted to use it as album art. I had no problem with that.

I never assign my art to any real permanence, so I was glad that he wanted to pick it up and use it for that purpose. After that, he kept having faith in me. Sometimes I'll come up with ideas for John and he won't be able to see my vision at all; it's sometimes hard for me to articulate my ideas. I'm not a wordsmith, I just push a pencil around. But usually he's surprised and pleased with what I come up with in the end.

Do you talk to him about what you're going to do before you do it?

Yes. Sometimes he'll pick something from images I've done, or other times he'll want to alter something I'm doing or funnel my path a little bit. But I like working with Thee Oh Sees because it allows me to participate in what I like a lot about album art, which is myth building. It's not a popular thing when you're an adult to still believe in the myth of a rock and roll band or the iconography that speaks about what a rock and roll band is, but for me, I like to retain a bit of naiveté and still believe in those myths.

One of the myths that really affected me was Cannibal Corpse's Back To Life. I remember seeing the album cover...this zombie ripping out its tendrils...and thinking, "Woah. They are making this music and they are eating flesh. Of course." I still retain these ideas, and this kind of mythology doesn't carry the music, but it bookends it.

It enhances the synaesthetic experience.

Yes, definitely. Sometimes, though, bands are lazy and they gravitate towards an aesthetic that they may feel is appropriate because they think it's a pathway to a goal, but I think a lot of the really great things that are created visually for bands are accidental or impulsive; less

deliberated.

On a similar note, another thing that I like about creating album art is considering visual branding. I grew up in the '80s and '90s when it was a formative time for mass commercialization. There were toys that would spin off into TV shows that would turn into snacks that would turn into theme park rides. You had all this visual branding on something that spread across so many mediums and physicalities. I would like to do that with my art but in a DIY way. I like the idea of art as a product if you have control over it, and it has nothing to do with money. I'm a working man's designer. It's like stealing back corporate control by mimicking their system, but for good. Take money and exploitation out of the equation and you can build your own neighborhood empire that's not harmful to people.

Also, the format of a record is great to work with. It's the perfect artifact. It's a great size, it doesn't take up too much room, but it's large enough so you can get lost in the depth of field; opening the gatefold and looking at a panoramic spread of art. You're indulging in all these visual aspects that are informed by or informing the auditory experience. It's almost the same as a music video, except that you can actually hold it. The more senses you use, the more appreciation you are going to have for something like that.

What other album art have you done?

I am working on a 7-inch for Young Prisms and I'm going to be working on a 7-inch for a band from Indiana called Burnt Ones. I also did a bunch of records for Thee Oh Sees, the Ty Segall and Mikal Cronin record Reverse Shark Attack, and just finished the newest Ty Segall record for Goner Records, Melted. [Editor's note: Emily Rose Epstein plays drums in Segall's band and played on Melted].

At this point, I want to keep it local or familiar. I don't want to charge anyone money or enter into that kind of arrangement with anyone I respect. I've turned down stuff that I didn't want to do because I felt like I wouldn't be able to represent them. Especially when people approach me and one of the first questions that they ask is, "How much would it be to..." I respect their bluntness, but if you're already putting it out there that that's the relationship you want to have with me, it lets me down and I lose interest automatically.

Do you listen to music when you're making art?

I'm really into guiding points and touchstones so when I'm making stuff, I always have something playing. I like to saturate myself with what I'm collaborating on, too, so I like to listen to an album I'm doing the art for, but I also like to tap into my mind to see what I can come up with psychically, so sometimes not having the entire puzzle worked out for you is nice too. When I worked with Ty, he'd say, "Check out this Beefheart cover...I'm going for that vibe," and I'd use it as a reference, but I want to destroy the idols. I'll use that Beefheart cover, but I'll tear it apart

to make something new from that.

Do you make music yourself?

I make music, but it doesn't come to me as easy as making something visually does. I started out playing music in really shitty, no-talent no wave bands where no one knew how to play their instruments. I didn't want to play with people who knew how to play music because I didn't want ability to enter into it. There is purity in not knowing what you're doing. But yes, playing music lends itself to my appreciation for art and its relationship with music and how they go hand in hand. They're both a craft. They're both labored over so I understand that.

Since your art has been opened up to a wider range of audiences by being featured on album covers, how has the public embraced your style? Have you seen it being appropriated by other people?

I really have blinders up to that. I kind of feel like imagery is ripe for the picking, and I don't have ownership over anything. If someone is ripping me off, then they should be ripping off someone better. The joke's on them. When I look back at anyone that I appreciated whether it's Raymond Pettibon or Gary Panter, they all defined their scene at their time, but people came along that did their own thing in reaction to those types of designs, or ripped things off and distorted it. I want to see more of that: people ripping me off.

No comments:

Post a Comment